Should Apple Do More to Curb Freemium Games?

By Rob Gordon 26 December 2015

After a seven-year-old boy spends nearly $6,000 on a Jurassic World freemium mobile game, we ask exactly who can do more to stop these events taking place in future.

Like it or loathe it, freemium gaming has become a huge part of the video game industry as a whole. Companies such as King, who were recently the target of a $5.9 billion buyout by Activision, have made huge profits out of addictive games with simple premises. Candy Crush Saga is one of the most popular mobile games in the world, whilst Supercell’s games (such as Clash of Clans and Boom Beach) also have a strong grip on the mobile market.

However, in the spite of the popularity of free-to-play games, and the fairly innocuous subject matter that many of them contain, these games have become some of the most contentious in gaming. This is down to the freemium business model that the developers and publishers have used to make their huge profits, with Kim Kardashian making $85 million from her mobile game in 2014 alone. The freemium model has been heavily criticized, with game creators accused of everything from cheapening the gaming experience to deliberately targeting an audience more likely to excessively spend money.

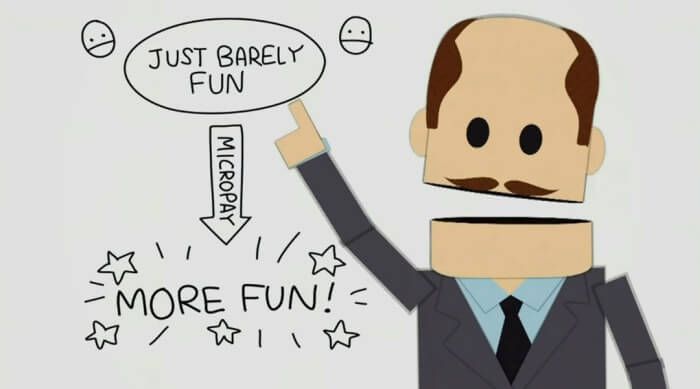

The latter point has caused much debate amongst the gaming community, particularly when such pop culture behemoths as South Park decide to take a satirical knife to the freemium practice. With a seemingly endless amount of money to be spent on in-app purchases, many have been left wondering about the ramifications that these games could have. Meanwhile, there have also been cases where users have spent money on another person’s account.

This was the case with seven-year-old Faisall Shugaa, who managed to rack up approximately £4,000 in in-app purchases for Jurassic World: The Game – which works out at just under $6,000. Young Faisall was using his father’s iPad at the time, and unbeknownst to the dad – a Mr. Mohamed Shugaa – his son knew his iTunes password. Within a week, Faisall had spent the incredible sum, with transactions ranging from £30.97 to £58.98.

Mr Shugaa immediately went back to Apple to request a refund for the amount spent, and was eventually granted one. However, Mr Shugaa raised the issue of whether Apple should have done more to prevent the transactions from going through in the first place. “Why didn’t they email me to check I knew these payments were being made? I got nothing from them,” he said.

Thankfully, it all worked out fine for both the Shugaas and for Apple, with the company able to organize a refund for the purchases. However, Mr Shugaa raises some interesting points about the role of Apple in protecting account holders from in-app purchases. Could the company have done more to recognize the irregular behaviour on his account and contact him regarding the transactions?

Mr Shugaa said that a simple email would have sufficed in order to get to the bottom of the problem at hand, potentially requesting a service similar to that used by banks and financial providers to protect against fraudulent account usage. Given that Apple is responsible for the content that is available on its store, even taking measures such as rejecting games with violent screenshots, some could argue that it should be required to protect its users from apps that could be easily exploited – with a prime candidate being freemium games. A response to this could be a team that contacts people when large sums of money have been spent, or an automated email system similar to the in-action iTunes app purchase alerts.

However, it’s a thin line between taking a proactive approach to protecting a customer base and unnecessarily interfering with users. Although Mr. Shugaa claims that, as an adult male, he would be unlikely to use a Jurassic Park mobile game, this assumption may not be accurate. After all, the age range of video game players has shifted dramatically over recent years, with a spike in popularity away from the child and teenage demographic that once personified the industry. Apple would not want to spend too much time meddling with how adults wish to spend their money.

With the particular case of the Shugaas, many may ask exactly where Faisall’s father was whilst his son was making these transactions. Given that he is only seven years old, many would expect that there was a more involved role in understanding exactly what Faisall was playing on the iOS device. Perhaps with a little more involvement, his father would have been able to stop this week-long in-app purchase spending spree.

The use of technology has become more and more important to children, with the use of tablets and computers in schools now a regular occurrence. In some places, games such as Minecraft are even being used as an educational tool, with every secondary school in Northern Ireland being given an educational build of the game. This brings with it even more problems, and perhaps even more of a responsibility to keep check on what content a son or daughter is using.

However, this is apparently easier said than done. According to a recent report from the BBC, parents are finding it increasingly difficult to curb the use of technology, with apparently 23% experiencing difficulty controlling a child’s screen usage. Mr. Shugaa may well have done more to stop Faisall from making these purchases, but there’s only so much he could do when Faisall was using his password without his knowledge.

Whilst content providers and parental figures no doubt have a significant role to play, others may argue that the creators themselves have helped cause this situation in the first place. It certainly seems at times that free-to-play games are specifically aiming to gain as much revenue as possible at the expense of the users themselves, and this has been corroborated by some of those working in the industry. A Gamasutra expose on pay-to-win games revealed just that, through an unnamed source who worked at a free-to-play developer.

According to the source, their prior company created games that “caused great harm to people’s lives.” This was not just an unwanted side-effect, however, as the source continues to state that the games are designed for addiction. Apparently, the company in question “chooses what to add to their games based on metrics that maximize players’ investments of time and money.” These players, known as ‘whales’ in the industry, are deliberately targeted through addictive mechanics, including the use of Skinner Box strategies in games such as Clash of Clans.

It’s particularly concerning, then, that a number of the top free-to-play games are based around franchises that specifically target children. Huge properties such as The Simpsons and Marvel have been on the receiving end of freemium mobile adaptations, with some in-app purchases reaching incredibly high costs. In the Electronic Arts-published The Simpsons: Tapped Out, for example, players can spend $199.99 on ‘donuts’ to buy in-game buildings and characters. With child-friendly freemium games, is it right to have such a high cost item a tap away?

The Jurassic World mobile game is certainly one of these cases. With the Jurassic Park franchise so beloved by children, it’s no wonder to see a seven-year old with no context of the situation happily spending money on in-game purchases. It’s hard to judge a child of that age of having no self-control, but one fix for future games of this nature could be an element of reflection from the designers themselves, by either limiting the cost of one-off items or providing something like a weekly limit for items purchased. It may go against business ideals, but it would certainly protect those most susceptible to the darker side of freemium mechanics.

That’s not to say that the developers themselves are the only people with an important place in this. In the end, it’s down to a number of factors. In spite of the role of technology in everyday life, Mr Shugaa perhaps should have been able to do more to stop his son from getting sucked into the pay-to-win cycle. However, there are still question marks over the morality of the mechanics used in free-to-play games – and perhaps even the content provider should do more to protect its customers. There are no easy answers, but hopefully going forward some of the issues with freemium gaming can be addressed.

Sources: BBC, Gamasutra